December 1, 2025

11 min

Kenneth D

January 15, 2026

12 min

Picture this: you wake up feeling fine, but a tiny sensor embedded in your chest has already detected subtle changes in your heart's pressure patterns. It wirelessly alerts your doctor, who adjusts your medication before you ever experience shortness of breath or swelling. Three weeks later, you're still living your normal life—while your neighbor with the same condition ends up in the emergency room.

This isn't science fiction anymore. It's the emerging reality of implantable biosensors, tiny devices that continuously monitor your body's internal chemistry, pressure, and oxygen levels. They're designed to spot trouble brewing long before symptoms appear, potentially transforming how we catch and treat everything from heart failure to surgical complications.

But here's the real question: Will these internal scouts actually change healthcare in the next decade, or are we still decades away from making them practical and affordable?

Implantable biosensors represent a fundamental shift from reactive to predictive healthcare. Instead of waiting for symptoms to drive you to a doctor's office, these devices continuously sample your body's internal environment—measuring glucose, pressure, oxygen, and other biomarkers that signal impending trouble.

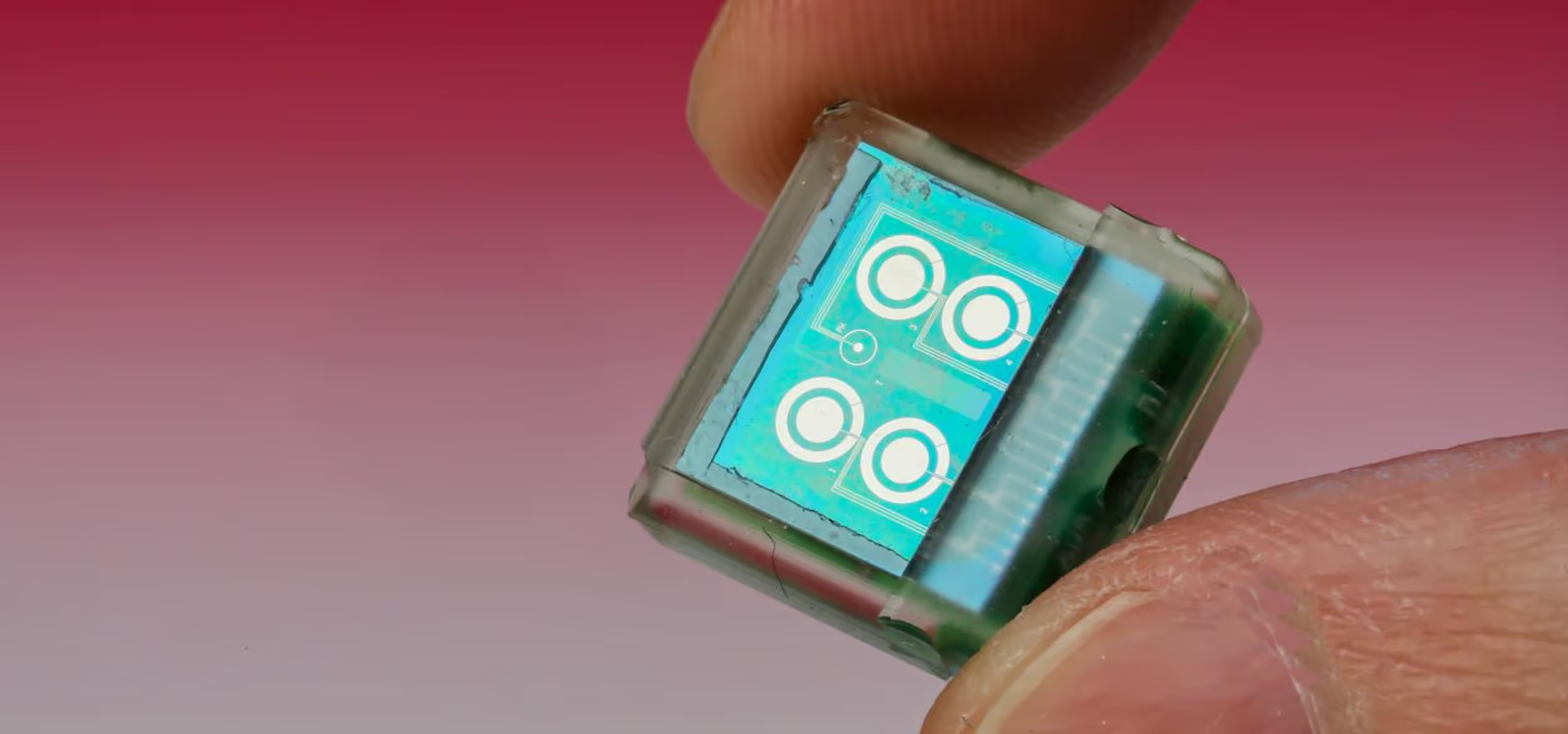

Current biosensors work through several established mechanisms. Electrochemical sensors detect glucose or other metabolites through enzymatic reactions. Pressure transducers measure hemodynamic forces in the heart or blood vessels. Optical sensors track oxygen saturation using fluorescence or phosphorescence. According to a 2023 review in Micromachines, these devices typically range from 1-15 millimeters in size and communicate wirelessly with external receivers.

The most mature application? Continuous glucose monitoring. The FDA-approved Eversense system uses a fluorescence-based sensor implanted subcutaneously that lasts up to 180 days. A 2021 randomized crossover trial published in Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice compared this implantable sensor against traditional transcutaneous monitors in 16 patients. The implantable device showed better overall accuracy (12.2% mean absolute relative difference) and remained functional 93.5% of the time over 12 weeks.

Heart failure management has emerged as biosensors' most compelling near-term application. The CardioMEMS HF System—a wireless pressure sensor implanted in the pulmonary artery—has generated the strongest clinical evidence to date. This matchstick-sized device measures pulmonary artery pressure daily, transmitting data wirelessly to clinicians who can adjust treatment before fluid builds up in the lungs.

The landmark CHAMPION trial, published in The Lancet in 2011, enrolled 550 heart failure patients and demonstrated a 28% reduction in heart failure hospitalizations over 15 months. A 2024 analysis in Global Cardiology confirmed these devices perform comparably in patients with and without atrial fibrillation—a critical finding since rhythm irregularities affect many heart failure patients. In January 2025, Medicare approved coverage for these devices under a Coverage with Evidence Development program, signaling regulatory acceptance of their clinical value.

Tissue oxygenation sensors address a critical clinical need: detecting when transplanted organs or surgical sites aren't getting enough blood flow. Anastomotic leakage—when surgical connections fail after intestinal surgery—occurs in 3-19% of colorectal procedures and carries mortality rates up to 40%. A 2021 study in Micromachines described platinum microelectrode arrays that detected acute intestinal ischemia in pigs with high accuracy, monitoring continuously for 45 hours after surgery.

More recently, researchers developed millimeter-scale ultrasound-powered oxygen sensors that work at depths up to 10 centimeters. Published in Nature Biotechnology in 2021, these sensors successfully monitored organ transplant oxygenation in sheep, addressing the critical 72-hour window when vascular complications typically occur.

Injectable hydrogel oxygen microsensors—roughly the size of a grain of rice—have been tested in over 90 humans, according to a comprehensive review in cellular engineering. These tissue-integrating sensors function for months to years, measuring oxygen fluctuations in conditions ranging from peripheral vascular disease to exercise physiology. In healthy volunteers, they detected oxygen changes with high correlation to commercial transcutaneous monitors (correlation coefficient 0.93) while showing greater sensitivity to physiological fluctuations.

The foreign body response remains biosensors' Achilles heel. When you implant anything into living tissue, the body encapsulates it in fibrous scar tissue within weeks. This fibrotic capsule blocks analyte diffusion and degrades sensor performance—a phenomenon extensively documented in a 2024 review in Micromachines.

Researchers have tackled this with several strategies. Dexamethasone-eluting coatings reduce inflammation. Porous hydrogel architectures encourage tissue integration rather than encapsulation. Some sensors deliberately create microenvironments that prevent protein fouling. Yet despite these advances, long-term stability beyond 6-12 months remains elusive for most biosensor types.

Power supply also constrains longevity. Battery-powered sensors eventually run out of juice. Passive radiofrequency-powered devices avoid batteries but require external interrogation and can't continuously transmit. Energy harvesting from body motion or ultrasound shows promise but remains in early development. The GlySens glucose sensor, tested in animals for over 500 days according to a 2010 Science Translational Medicine report, uses oxygen consumption to measure glucose without requiring external power—an elegant solution that hasn't yet reached widespread human use.

While researchers have demonstrated functional sensors for glucose, pressure, oxygen, pH, lactate, and numerous other analytes, the clinical translation bottleneck is real. Only a handful of implantable biosensors have achieved FDA approval and commercial adoption:

The pattern is clear: sensors that address acute life-threatening conditions with strong hospital economics gain traction. Sensors for chronic metabolic monitoring face steeper adoption barriers despite potentially larger patient populations.

Academic medicine recognizes biosensors' potential but demands rigorous evidence. According to the American Heart Association's 2024 guidelines, implantable hemodynamic monitors like CardioMEMS receive Class IIa recommendations (should be considered) for carefully selected heart failure patients. The evidence bar is high: multi-center randomized controlled trials showing not just sensor accuracy but actual clinical outcomes—reduced hospitalizations, improved survival, better quality of life.

The Cleveland Clinic's position reflects this measured approach. They've adopted CardioMEMS for appropriate heart failure patients but emphasize it complements—doesn't replace—careful clinical assessment and medication management. Harvard Health notes that biosensors work best when integrated into comprehensive disease management programs with responsive clinical teams.

Cost-effectiveness analyses reveal the economic calculus. A heart failure hospitalization averages $13,000. CardioMEMS devices cost roughly $17,000-20,000 for implantation plus monitoring infrastructure. If the device prevents just 1-2 hospitalizations over its lifespan, it breaks even. Early health economic models suggest favorable cost-effectiveness in high-risk heart failure populations, though real-world data are still accumulating.

For glucose monitoring, mainstream medicine remains divided. The American Diabetes Association acknowledges continuous glucose monitoring's benefits but notes most evidence comes from short-term transcutaneous sensors. Implantable sensors offer convenience but haven't demonstrated superior glucose control or complication reduction compared to existing options. Given similar efficacy and higher surgical risk, many endocrinologists reserve implantable CGM for patients with adherence challenges or severe hypoglycemia unawareness.

Mayo Clinic researchers highlight a crucial limitation: most biosensors measure correlation, not causation. Elevated pulmonary artery pressure correlates with heart failure decompensation, but the pressure itself isn't the target—the underlying fluid retention and cardiac dysfunction are. Sensors provide data, but clinical judgment still determines intervention.

The wellness and integrative medicine community sees biosensors through a different lens: continuous personalized data streams enabling optimization rather than just disease management.

Dr. Mark Hyman, a functional medicine leader, frequently discusses wearable biosensors' potential to reveal individual metabolic responses. Implantable versions could theoretically provide even more precise insights—measuring interstitial glucose patterns, tissue oxygenation during exercise, real-time inflammatory markers. The vision: move beyond treating disease to actively optimizing health.

Some integrative practitioners imagine biosensors detecting early inflammation, oxidative stress, or metabolic dysfunction before conventional medicine would recognize pathology. They reference studies showing interstitial glucose fluctuations differ from blood glucose—potentially revealing insulin resistance patterns invisible to standard testing. An implanted sensor continuously monitoring metabolic markers could guide personalized nutrition and supplement interventions.

The biohacking community has enthusiastically embraced CGM, with non-diabetics using sensors to optimize performance and longevity. Implantable versions appeal to this mindset's logical extreme: permanent personalized biomonitoring. They envision future sensors measuring cortisol, inflammatory cytokines, hormone levels, nutrient status—creating comprehensive real-time metabolic dashboards.

However, this perspective largely overlooks the sobering reality that most biosensor research focuses on acute clinical applications—heart failure, surgical monitoring, diabetes management. The infrastructure for translating sensors into wellness optimization tools doesn't yet exist. Insurance won't cover biosensors for optimization in healthy people. The regulatory pathway for "enhancement" rather than treatment remains unclear.

More fundamentally, having more data doesn't automatically improve health. Several studies document "alert fatigue" where continuous monitoring paradoxically worsens outcomes because patients and clinicians become desensitized to warnings. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health warns that "quantified self" approaches can promote anxiety and medicalization of normal variation rather than empowerment.

Social media's health technology discourse reveals a pattern: oscillation between breathless optimism and frustrated skepticism.

Tech YouTubers like MKBHD have covered wearable biosensors extensively, noting their rapid improvement but questioning when implantables will become practical. Comments sections reveal public interest paired with concerns: "Will this require surgery?" "How much will it cost?" "What happens when the battery dies inside me?"

Instagram wellness influencers (@drmeganramos, @glucosegoddess) frequently discuss CGM for metabolic health optimization. Their followers ask about implantable options but often retreat when learning about minor surgical procedures and several-thousand-dollar costs. The convenience appeal is strong; the invasiveness barrier is stronger.

TikTok medical creators like @doctorjessmedia emphasize the difference between research headlines and clinical reality. A viral video explaining biosensor technology might generate millions of views, but the comments consistently ask: "When can I actually get this?" The answer—"Maybe in 5-10 years for most applications, if you have the right medical condition"—disappoints audiences expecting imminent transformation.

Critics raise valid concerns amplified in online spaces. Privacy activists worry about continuous biosensor data streams. Who owns this information? Can employers or insurers access it? Could hackers compromise implanted devices? These aren't theoretical—researchers have demonstrated wireless exploits of cardiac implants, though manufacturers have since improved security.

Some influencers promote unfounded fears. Claims that biosensors "change your DNA" or "track your every move" circulate despite lacking scientific basis. Conversely, breathless promotion as "the end of disease" overstates near-term potential.

The most informed public discourse recognizes biosensors as powerful but incremental advances—most valuable for specific high-risk conditions, less transformative for general wellness than marketing suggests.

Three clear conclusions emerge from examining these perspectives:

First, implantable biosensors work—but only for specific applications where the clinical need justifies invasiveness. Heart failure pressure monitoring has crossed this threshold with strong evidence and regulatory approval. Glucose monitoring is transitioning from research to practice, though transcutaneous sensors may ultimately prove "good enough" for most patients. Oxygen monitoring for surgical complications shows enormous promise but awaits large-scale validation trials.

Second, the technology exists; the barriers are biological and economic, not engineering. We can build sensors that measure virtually any biomarker with remarkable accuracy. The limiting factors are foreign body response degrading long-term performance, power supply constraints, and healthcare economics. A sensor measuring interleukin-6 to predict sepsis might be technically feasible but economically and logistically impractical.

Third, biosensors enable better decisions but don't make decisions themselves. Even perfect continuous data requires human judgment about intervention thresholds, treatment adjustments, and balancing risks and benefits. The CardioMEMS success story involves both the sensor and the responsive clinical infrastructure around it.

The divergence between wellness optimism and medical pragmatism reveals differing value propositions. Mainstream medicine demands evidence that biosensors improve outcomes—fewer hospitalizations, better survival, lower costs. Integrative and consumer perspectives value insight and empowerment even without demonstrated outcome improvements. This philosophical gap will shape how biosensors deploy over the next decade.

The alert fatigue and data anxiety concerns are legitimate. More information isn't automatically beneficial; it must be actionable and presented appropriately. Studies of CGM in non-diabetics show mixed psychological effects—some users feel empowered, others develop disordered eating patterns. Implantable sensors amplify these dynamics by making monitoring permanent and less escapable.

Cost remains the elephant in the room. CardioMEMS costs $17,000-20,000 for implantation. Even after regulatory approval, adoption requires insurance coverage, which Medicare has finally provided but with significant restrictions. Commercial insurers are following slowly. For conditions without comparable hospitalization costs, the economic case becomes much harder.

If implantable biosensors are to fulfill their promise, research must address five critical areas:

The holy grail is sensors that integrate with tissue rather than triggering encapsulation. Promising approaches include:

Several teams are exploring whether pre-conditioning implant sites with growth factors or stem cells could create more favorable tissue environments. Others investigate whether smaller sensors—at the sub-millimeter scale—might evade robust foreign body responses.

Energy remains a fundamental constraint. Future directions include:

Wireless communication standards specifically for biomedical implants are emerging. The IEEE 802.15.6 standard addresses body area networks, but practical deployment at scale requires infrastructure most hospitals lack.

Rather than implanting separate devices for glucose, oxygen, lactate, and pH, the next generation should measure multiple biomarkers from one implant. Microfluidic "lab-on-a-chip" architectures show promise, integrating enzyme electrodes, optical sensors, and ion-selective membranes on single platforms. The challenge is maintaining accuracy when sensors share space and influence each other's microenvironments.

Continuous data streams overwhelm human processing capacity. Machine learning algorithms must identify meaningful patterns while filtering noise and normal variation. Promising directions include:

Several research teams are developing "digital twins"—personalized computational models that simulate individual patients' physiology and predict responses to interventions based on biosensor data.

Beyond heart failure, where economic benefits are established, other conditions need rigorous cost-effectiveness analyses. Post-surgical oxygen monitoring might prevent catastrophic leaks, but what's the number-needed-to-monitor? How much does continuous monitoring cost versus current periodic assessments? These pragmatic questions determine adoption more than technical capability.

Studies comparing biosensor-guided care against current standard of care—powered for clinical endpoints like hospitalizations and mortality, not just sensor accuracy—remain surprisingly rare. The FDA and CMS are increasingly requiring outcome evidence rather than accepting surrogate measures.

Here's what you actually need to know about implantable biosensors right now:

For heart failure patients: Implantable pressure monitors are proven technology today—not tomorrow. If you have chronic heart failure with repeated hospitalizations despite optimal medication, ask your cardiologist about CardioMEMS. The evidence supports it, Medicare covers it, and it could genuinely reduce your time in the hospital.

For diabetes management: Implantable CGM exists but isn't clearly superior to newer transcutaneous sensors that last 10-14 days and don't require surgical implantation. Unless you have specific issues with adhesive sensors or severe hypoglycemia unawareness, transcutaneous options are probably better for now.

For surgical monitoring: Oxygen sensors for transplant and anastomotic monitoring are coming but aren't widely available yet. If you're having complex colorectal surgery or organ transplantation at a major academic center, ask whether they're participating in biosensor trials—early access might be possible.

For general wellness optimization: Implantable biosensors targeting healthy people are at least 5-10 years away from practical reality. The infrastructure doesn't exist, the economic model doesn't work, and frankly, non-invasive wearables are advancing rapidly enough that implantables may never make sense for this population.

The 5-10 year outlook: Expect expansion in post-surgical monitoring (oxygen, pressure) and potentially cancer therapy monitoring (tumor microenvironment sensors). Chronic disease management will likely stay dominated by external wearables unless implantable sensors dramatically improve longevity and reduce costs.

Technology barriers: The science exists; the challenges are biocompatibility (foreign body response), power supply, and cost. These are solvable but require sustained research investment and clinical validation.

Cost-effectiveness reality: Unless you have a condition where hospitalization costs exceed sensor costs, insurance won't cover it. Heart failure qualifies. Most other conditions don't yet have the economic case closed.

Credibility Rating: 6/10

Implantable biosensors represent proven technology for specific high-risk conditions—particularly heart failure—where continuous monitoring demonstrably improves outcomes. The next 5-10 years will see gradual expansion into post-surgical monitoring and possibly cancer therapy tracking. However, the promise of ubiquitous internal health monitoring for disease prevention remains distant. The barriers aren't primarily technological; they're biological (foreign body response), economic (cost-effectiveness), and systemic (healthcare infrastructure).

For most people, implantable biosensors remain an intriguing future possibility rather than a current practical option. If you have heart failure with repeated hospitalizations or brittle diabetes despite optimal management, they're worth serious discussion with your physician today. Otherwise, the wearable sensor revolution offers more immediate benefits with far less invasiveness.

The technology will get better—sensors will last longer, cost less, and measure more biomarkers. But transforming healthcare requires solving not just engineering challenges but the harder problems of biology, economics, and healthcare delivery systems. That transformation is happening, just more gradually than the headlines suggest.

Disclaimer: Always consult a healthcare professional before making significant dietary changes. This content includes personal opinions and interpretations based on available sources and should not replace medical advice. This content includes interpretation of available research and should not replace medical advice. Although the data found in this blog and infographic has been produced and processed from sources believed to be reliable, no warranty expressed or implied can be made regarding the accuracy, completeness, legality or reliability of any such information. This disclaimer applies to any uses of the information whether isolated or aggregate uses thereof.